My last article documented the

funding of the March 1917 Revolution in Russia.[1] The primary financier of the

Russian revolutionary movement 1905–1917 was Jacob Schiff, of Kuhn Loeb and

Co., New York. In particular Schiff had provided the money for the distribution

of revolutionary propaganda among Russians prisoners-of-war in Japan in 1905 by

the American journalist George Kennan who, more than any other individual, was

responsible for turning American public and official opinion against Czarist

Russia. Kennan subsequently related that it was thanks to Schiff that 50,000

Russian soldiers were revolutionized and formed the cadres that laid the basis

for the March 1917 Revolution and, we might add–either directly or

indirectly–the consequent Bolshevik coup of November. The reaction of

bankers from Wall Street and The City towards the overthrow of the Czar was

enthusiastic.

This article deals with the funding of the subsequent Bolshevik coup

eight months later which, as paradoxical as it might seem to those who know

nothing of history other than the orthodox version, was also greeted cordially

by banking circles in Wall Street and elsewhere.

Apologists for the bankers and other highly-placed individuals who

supported the Bolsheviks from the earliest stages of the communist takeover,

either diplomatically or financially, justify the support for this mass

application of psychopathology as being motivated by patriotic sentiment, in

trying to thwart German influence over the Bolsheviks and to keep Russia in the

war against Germany. Because Lenin and his entourage had been able to enter

Russia courtesy of the German High Command on the basis that a Bolshevik regime

would withdraw Russia from the war, Wall Street capitalists explained that

their patronage of the Bolsheviks was motivated by the highest ideals of

pro-Allied sentiment. Hence, William Boyce Thompson in particular stated that

by funding Bolshevik propaganda for distribution in Germany and Austria this

would undermine the war effort of those countries, while his assistance to the

Bolsheviks in Russia was designed to swing them in favor of the Allies.

These protestations of patriotic motivations ring hollow. International

banking is precisely what it is called–international, or globalist

as such forms of capitalism are now called. Not only have these banking forms

and other forms of big business had overlapping directorships and investments

for generations, but they are often related through intermarriage. While Max

Warburg of the Warburg banking house in Germany advised the Kaiser and while

the German Government arranged for funding and safe passage of Lenin and his

entourage from Switzerland across Germany to Russia;[2] his brother Paul,[3] a

partner of Jacob Schiff’s at Wall Street, looked after the family interests in

New York. The primary factor that was behind the bankers’ support for the

Bolsheviks whether from London,[4] New York, Stockholm,[5] or Berlin, was to

open up the underdeveloped resources of Russia to the world market, just as in

our own day George Soros, the money speculator, funds the so-called “color

revolutions” to bring about “regime change” that facilitates the opening up of

resources to global exploitation. Hence there can no longer be any doubt that

international capital a plays a major role in fomenting revolutions, because

Soros plays the well-known modern-day equivalent of Jacob Schiff.

Recognition of Bolsheviks Pushed by Bankers

This aim of international finance, whether centered

in Germany, England or the USA, to open up Russia to capitalist exploitation by

supporting the Bolsheviks, was widely commented on at the time by a diversity

of well-informed sources, including Allied intelligence agencies, and of

particular interest by two very different individuals, Henry Wickham Steed,

On May 1, 1922 The New York Times reported that Gompers, reacting to

negotiations at the international economic conference at Genoa, declared that a

group of “predatory international financiers” were working for the recognition

of the Bolshevik regime for the opening up of resources for exploitation.

Despite the rhetoric by New York and London bankers during the war that a

Russian revolution would serve the Allied cause, Gompers opined that this was

an “Anglo-American-German banking group,” and that they were “international

bankers” who did not adhere to any national allegiance. He also noted that

prominent Americans who had a history of anti-labor attitudes were advocating

recognition of the Bolshevik regime.[6]

What Gompers claimed, was similarly expressed by Henry Wickham Steed of The

London Times, based on his observations. In a first-hand account of the

Paris Peace Conference of 1919, Steed stated that proceedings were interrupted

by the return from Moscow of William C. Bullitt and Lincoln Steffens, “who had

been sent to Russia towards the middle of February by Colonel House and Mr.

Lansing, for the purpose of studying conditions, political and economic,

therein for the benefit of the American Commissioners plenipotentiary to

negotiate peace.”[7] Steed also refers to British Prime Minister Lloyd George

as being likely to have known of the Mission and its purpose. Steed stated that

international finance was behind the move for recognition of the Bolshevik

regime and other moves in favor of the Bolsheviks, and specifically identified

Jacob Schiff of Kuhn, Loeb & Co., New York, as one of the principal bankers

“eager to secure recognition”:

Potent international financial interests were at work in favor of the

immediate recognition of the Bolshevists. Those influences had been largely

responsible for the Anglo-American proposal in January to call Bolshevist

representatives to Paris at the beginning of the Peace Conference—a proposal

which had failed after having been transformed into a suggestion for a

Conference with the Bolshevists at Prinkipo. . . . The well-known American

Jewish banker, Mr. Jacob Schiff, was known to be anxious to secure recognition

for the Bolshevists . . .[8]

In return for diplomatic recognition, Tchitcherin, the Bolshevist

Commissary for Foreign Affairs, was offering “extensive commercial and economic

concessions.”Wickham Steed with the support of The Times’ proprietor, Lord

Northcliffe, exposed the machinations of international finance to obtain the

recognition of the Bolshevik regime, which still had a very uncertain future.

Steed related that he was called upon by US President Wilson’s primary

adviser, Edward Mandel House, who was concerned at Steed’s exposé of the

relationship between Bolshevists and international financers:

That day Colonel House asked me to call upon him. I found him worried both by

my criticism of any recognition of the Bolshevists and by the certainty, which

he had not previously realized, that if the President were to recognize the

Bolshevists in return for commercial concessions his whole “idealism” would be

hopelessly compromised as commercialism in disguise. I pointed out to him that

not only would Wilson be utterly discredited but that the League of Nations

would go by the board, because all the small peoples and many of the big

peoples of Europe would be unable to resist the Bolshevism which Wilson would

have accredited.[9]

Steed stated to House that it was Jacob Schiff, Warburg and other bankers

who were behind the diplomatic moves in favor of the Bolsheviks:

I insisted that, unknown to him, the prime movers were Jacob Schiff,

Warburg, and other international financiers, who wished above all to bolster up

the Jewish Bolshevists in order to secure a field for German and Jewish

exploitation of Russia.[10]

Steed here indicates an uncharacteristic naïveté in thinking that House would

not have known of the plans of Schiff, Warburg, et al. House was

throughout his career close to these bankers and was involved with them in

setting up a war-time think tank called The Inquiry, and following the war the

creation of the Council on Foreign Relations, in order to shape an

internationalist post-war foreign policy. It was Schiff and Paul Warburg and

other Wall Street bankers who called on House in 1913 to get House’s support

for the creation of the Federal Reserve Bank.[11]House in Machiavellian manner asked Steed to compromise; to support

humanitarian aid supposedly for the benefit of all Russians. Steed agreed to

consider this, but soon after talking with House found out that British Prime

Minister Lloyd George and Wilson were to proceed with recognition the following

day. Steed therefore wrote the leading article for the Paris Daily Mail

of March 28th, exposing the maneuvers and asking how a pro-Bolshevik attitude

was consistent with Pres. Wilson’s declared moral principles for the post-war

world?

. . . Who are the tempters that would dare whisper into the ears of the

Allied and Associated Governments? They are not far removed from the men who

preached peace with profitable dishonour to the British people in July, 1914.

They are akin to, if not identical with, the men who sent Trotsky and some

scores of associate desperadoes to ruin the Russian Revolution as a democratic,

anti-German force in the spring of 1917.[12]

Here Steed does not seem to have been aware that some of the same bankers

who were supporting the Bolsheviks had also supported the March Revolution.

Charles Crane,[13] who had recently talked with President Wilson, told

Steed that Wilson was about to recognize the Bolsheviks, which would result in

a negative public opinion in the USA and destroy Wilson’s post-War

internationalist aims. Significantly Crane also identified the pro-Bolshevik

faction as being that of Big Business, stating to Steed: “Our people at home

will certainly not stand for the recognition of the Bolshevists at the bidding

of Wall Street.” Steed was again seen by House, who stated that Steed’s article

in the Paris Daily Mail, “had got under the President’s hide.” House

asked that Steed postpone further exposés in the press, and again raised the

prospect of recognition based on humanitarian aid. Lloyd George was also

greatly perturbed by Steed’s articles in the Daily Mail and complained

that he could not undertake a “sensible” policy towards the Bolsheviks while

the press had an anti-Bolshevik attitude.[14]

Thompson and the American Red Cross Mission

As mentioned, House attempted to persuade Steed on

the idea of relations with Bolshevik Russia ostensibly for the purpose of

humanitarian aid for the Russian people. This had already been undertaken just

after the Bolshevik Revolution, when the regime was far from certain, under the guise of the

American Red Cross Mission. Col. William Boyce Thompson, a director of the NY

Federal Reserve Bank, organized and largely funded the Mission, with other

funding coming from International Harvester, which gave $200,000. The so-called

Red Cross Mission was largely comprised of business personnel, and was

according to Thompson’s assistant, Cornelius Kelleher, “nothing but a mask” for

business interests.[15] Of the 24 members, five were doctors and two were

medical researchers. The rest were lawyers and businessmen associated with Wall

Street. Dr. Billings nominally headed the Mission.[16] Prof. Antony Sutton of

the Hoover Institute stated that the Mission provided assistance for

revolutionaries:

We know from the files of the U.S. embassy in Petrograd that the U.S. Red

Cross gave 4,000 rubles to Prince Lvoff, president of the Council of Ministers,

for “relief of revolutionists” and 10,000 rubles in two payments to Kerensky

for “relief of political refugees.”[17]

The original intention of the Mission, hastily organized by Thompson in

light of revolutionary events, was ‘”nothing less than to shore up the

Provisional regime,” according to the historian William Harlane Hale, formerly

of the United States Foreign Service.[18] The support for the social revolutionaries

indicates that the same bankers who backed the Kerensky regime and the March

Revolution also supported the Bolsheviks, and it seems reasonable to opine that

these financiers considered Kerensky a mere prelude for the Bolshevik coup, as

the following indicates.

Thompson set himself up in royal manner in Petrograd reporting directly to

Pres. Wilson and bypassing US Ambassador Francis. Thompson provided funds from

his own money, first to the Social Revolutionaries, to whom he gave one million

rubles,[19] and shortly after $1,000,000 to the Bolsheviks to spread their

propaganda to Germany and Austria.[20] Thompson met Thomas Lamont

of J. P. Morgan Co. in London to persuade the British War Cabinet to drop its

anti-Bolshevik policy. On his return to the USA Thompson undertook a tour

advocating US recognition of the Bolsheviks.[21] Thompson’s deputy Raymond

Robbins had been pressing for recognition of the Bolsheviks, and Thompson

agreed that the Kerensky regime was doomed and consequently “sped to Washington

to try and swing the Administration onto a new policy track,” meeting

resistance from Wilson, who was being pressure by Ambassador Francis.[22]

Such was Thompson’s enthusiasm for Bolshevism that he was nicknamed “the

Bolshevik of Wall Street” by his fellow plutocrats. Thompson gave a lengthy

interview with The New York Times just after his four month tour with

the American Red Cross Mission, lauding the Bolsheviks and assuring the

American public that the Bolsheviks were not about to make a separate peace

with Germany.[23] The article is an interesting indication of how Wall Street

viewed their supposedly “deadly enemies,” the Bolsheviks, at a time when their

position was very precarious. Thompson stated that while the “reactionaries,”

if they assumed power, might seek peace with Germany, the Bolsheviki would not.

“His opinion is that Russia needs America, that America must stand by Russia,”

stated the Times. Thompson is quoted: “The Bolsheviki peace aims are the

same as those of the Untied States.” Thompson alluded to Wilson’s speech to the

United States Congress on Russia as “a wonderful meeting of the situation,” but

that the American public “know very little about the Bolsheviki.” The Times

stated:

Colonel Thompson is a banker and a capitalist, and he has large

manufacturing interests. He is not a sentimentalist nor a “radical.” But he has

come back from his official visit to Russia in absolute sympathy with the

Russian democracy as represented by the Bolsheviki at present.

Hence at this time Thompson was trying to sell the Bolsheviks as

“democrats,” implying that they were part of the same movement as the Kerensky

regime that they had overthrown. While Thompson did not consider Bolshevism the

final form of government, he did see it as the most promising step towards a

“representative government” and that it was the “duty” of the USA to

“sympathize” with and “aid” Russia “through her days of crisis.” He stated that

in reply to surprise at his pro-Bolshevik sentiments he did not mind being

called “red” if that meant sympathy for 170,000,000 people “struggling for

liberty and fair living.” Thompson also saw that while the Bolsheviki had

entered a “truce” with Germany, they were also spreading Bolshevik doctrines

among the German people, which Thompson called “their ideals of freedom” and

their “propaganda of democracy.” Thompson lauded the Bolshevik Government as

being the equivalent to America’s democracy, stating:

Thompson saw the prospects of the Bolshevik Government being transformed as

it incorporated a more Centrist position and included employers. If Bolshevism

did not proceed thus, then “God help the world,” warned Thompson. Given that

this was a time when Lenin and Trotsky held sway over the regime, subsequently

to become the most enthusiastic advocates of opening Russia up to foreign

capital (New Economic Policy) prospects seemed good for a joint

Capitalist-Bolshevik venture with no indication that an upstart named Stalin

would throw a spanner in the works.

The Times article ends: “At home in New York, the Colonel has

received the good-natured title of ‘the Bolshevik of Wall Street.’”[24] It was

against this background that it can now be understood why labor leader Samuel

Gompers denounced Bolshevism as a tool of “predatory international finance,”

while arch-capitalist Thompson lauded it as “a government of working men.”

The Council on Foreign Relations Report

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) had been established in 1921 by

President Wilson’s chief adviser Edward Mandel House out of a previous think tank

called The Inquiry, formed in 1917–1918 to advise President Wilson on the Paris

Peace Conference of 1919. It was this conference about which Steed had detailed

his observations when he stated that there were financial interests trying to

secure the recognition of the Bolsheviks.[25]

Peter Grose in his semi-official history of the CFR writes of it as a think

tank combining academe and big business that had emerged from The Inquiry

group.[26] Therefore the CFR report on Soviet Russia at this early period is

instructive as to the relationship that influential sections of the US

Establishment wished to pursue in regard to the Bolshevik regime. Grosse writes

of this period:

However, financial interests had already moved into Soviet Russia from the

beginning of the Bolshevik regime.

The Vanderlip Concession

H. G. Wells, historian, novelist, and Fabian-socialist, observed first-hand

the relationship between Communism and big business when he had visited

Bolshevik Russia. Travelling to Russia in 1920 where he interviewed Lenin and

other Bolshevik leaders, Wells hoped that the Western Powers and in particular

the USA would come to the Soviets’ aid. Wells also met there “Mr. Vanderlip”

who was negotiating business contracts with the Soviets. Wells commented of the

situation he would like to see developing, and as a self-described

“collectivist” made a telling observation on the relationship between Communism

and “Big Business”:

The only Power capable of playing this role of

eleventh-hour helper to Russia single-handed is the United States of America.

That is why I find the adventure of the enterprising and imaginative Mr.

Vanderlip very significant. I doubt the conclusiveness of his negotiations;

they are probably only the opening phase of a discussion of the Russian problem

upon a new basis

that may lead it at last to a comprehensive world treatment of this situation.

Other Powers than the United States will, in the present phase of

world-exhaustion, need to combine before they can be of any effective use to

Russia. Big business is by no means antipathetic to Communism. The larger big

business grows the more it approximates to Collectivism. It is the upper road

of the few instead of the lower road of the masses to Collectivism.[28]

In

addressing concerns that were being expressed among Bolshevik Party “activists”

at a meeting of the Moscow Organization of the party, Lenin sought to reassure

them that the Government was not selling out to foreign capitalism, but that,

in view of what Lenin believed to be an inevitable war between the USA and

Japan, a US interest in Kamchatka would be favorable to Soviet Russia as a

defensive position against Japan. Such strategic considerations on the part of

the US, it might be added, were also more relevant to US and other forms of

so-called “intervention” during the Russian Civil War between the Red and the

White Armies, than any desire to help the Whites overturn the Bolsheviks, let

alone restore Czarism. Lenin said of Vanderlip to the Bolshevik cadres:

We must take

advantage of the situation that has arisen. That is the whole purpose of the

Kamchatka concessions. We have had a visit from Vanderlip, a distant relative

of the well-known multimillionaire, if he is to he believed; but since our

intelligence service, although splendidly organized, unfortunately does not yet

extend to the United States of America, we have not yet established the exact

kinship of these Vanderlips. Some even say there is no kinship at all. I do not

presume to judge: my knowledge is confined to having read a book by Vanderlip,

not the one that was in our country and is said to be such a very important

person that he has been received with all the honors by kings and

ministers—from which one must infer that his pocket is very well lined indeed.

He spoke to them in the way people discuss matters at meetings such as ours,

for instance, and told then in the calmest tones how Europe should be restored.

If ministers spoke to him with so much respect, it must mean that Vanderlip is

in touch with the multimillionaires.[29]

Of the

meeting with Vanderlip, Lenin indicated that it was based on a secret diplomacy

that was being denied by the US Administration, while Vandrelip returned to the

USA, like other capitalists such as Thompson, praising the Bolsheviks. Lenin

continued:

This

mysterious Vanderlip was in fact Washington Vanderlip who had, according to

Armand Hammer, come to Russia in 1919, although even Hammer does not seem to

have known much of the matter.[31] Lenin’s rationalizations in trying to

justify concessions to foreign capitalists to the “Moscow activists” in 1920

seem disingenuous and less than forthcoming. Washington Vanderlip was an

engineer whose negotiations with Russia drew considerable attention in the USA.

The New York Times wrote that Vanderlip, speaking from Russia, denied

reports of Lenin’s speech to “Moscow activists” that the concessions would

serve Bolshevik geopolitical interests, with Vanderlip declaring that he had

established a common frontier between the USA and Russia and that trade

relations must be immediately restored.[32] The New York Times reporting

in 1922: “The exploration of Kamchatka for oil as soon as trade relations

between this country and Russia are established was assured today when the

Standard Oil Company of California purchased one-quarter of the stock in the

Vanderlip syndicate.” This gave Standard Oil exclusive leases on any syndicate

lands on which oil was found. The Vanderlip syndicate comprised sixty-four

units. The Standard Oil Company has just purchased sixteen units. However, the

Vanderlip concessions could not come into effect until Soviet Russia was

recognized by the USA.[33]

It is little

wonder then that US capitalists were eager to see the recognition of the Soviet

regime.

Bolshevik

Bankers

In 1922

Soviet Russia’s first international bank was created, Ruskombank, headed by

Olof Aschberg of the Nye Banken, Stockholm, Sweden. The predominant capital

represented in the bank was British. The foreign director of Ruskombank was Max

May, vice president of the Guaranty Trust Company.[35] Similarly to “the

Bolshevik of Wall Street,” William Boyce Thompson, Aschberg was known as the

“Bolshevik banker” for his close involvement with banking interests that had

channeled funds to the Bolsheviks.

Guaranty

Trust Company became intimately involved with Soviet economic transactions. A Scotland

Yard Intelligence Report stated as early as 1919 the connection between

Guaranty Trust and Ludwig C. A. K. Martens, head of the Soviet Bureau in New York

when the bureau was established that year.[36] When representatives of the Lusk

Committee investigating Bolshevik activities in the USA raided the Soviet

Bureau offices on May 7, 1919, files of communications with almost a thousand

firms were found. Basil H. Thompson of Scotland Yard in a special report stated

that despite denials, there was evidence in the seized files that the Soviet

Bureau was being funded by Guaranty Trust Company.[37] The significance of the

Guaranty Trust Company was that it was part of the J. P. Morgan economic

empire, which Dr. Sutton shows in his study to have been a major player in

economic relations with Soviet Russia from its early days. It was also J. P.

Morgan interests that predominated in the formation of a consortium, the

American International Corporation (AIC), which was another source eager to

secure the recognition of the still embryonic Soviet state. Interests

represented in the directorship of the American International Corporation (AIC)

included: National City Bank; General Electric; Du Pont; Kuhn, Loeb and Co.;

Rockefeller; Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Ingersoll-Rand; Hanover National

Bank, etc.[38]

The AIC’s

representative in Russia at the time of the revolutionary tumult was its

executive secretary William Franklin Sands, who was asked by US Secretary of

State Robert Lansing for a report on the situation and what the US response

should be. Sands’ attitude toward the Bolsheviks was, like that of Thompson,

enthusiastic. Sands wrote a memorandum to Lansing in January 1918, at a time

when the Bolshevik hold was still far from sure, that there had already been

too much of a delay by the USA in recognizing the Bolshevik regime such as it

existed. The USA had to make up for “lost time,” and like Thompson, Sands considered

the Bolshevik Revolution to be analogous to the American Revolution.[39] In

July 1918 Sands wrote to US Treasury Secretary McAdoo that a commission should

be established by private interests with government backing, to provide

“economic assistance to Russia.”[40]

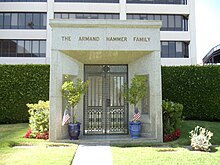

Armand

Hammer

One of those

closely associated with Ludwig Martens and the Soviet Bureau was Dr. Julius

Hammer, an emigrant from Russia who was a founder of the Communist Party USA.

There is evidence that Julius Hammer was the host to Leon Trotsky when the

latter with his family arrived in New York in 1917, and that it was Dr.

Hammer’s chauffeured car that provided transport to Natalia and the Trotsky

children. The Trotskys were met on disembarkation at the New York dock by

Arthur Concors, a director of the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society,

whose advisory board included Jacob Schiff of Kuhn, Loeb and Co.[41] Dr. Hammer

was the “primary owner of Allied Drug and Chemical Co.,” and “one of those not

so rare creatures, a radical Marxist turned wealthy entrepreneur,” who lived an

opulent lifestyle, according to Professor Spence.[42] Another financier linked

to Trotsky was his own uncle, banker Abram Zhivotovskii, who was associated

with numerous financial interests including those of Olof Aschberg.[43]

The intimate association of the Hammer family with

Soviet Russia was to be maintained from start to finish, with an interlude of

withdrawal during the Stalinist period. Julius’ son Armand, chairman of

Occidental Petroleum Corporation, wThe AIC’s

representative in Russia at the time of the revolutionary tumult was its

executive secretary William Franklin Sands, who was asked by US Secretary of

State Robert Lansing for a report on the situation and what the US response

should be. Sands’ attitude toward the Bolsheviks was, like that of Thompson,

enthusiastic. Sands wrote a memorandum to Lansing in January 1918, at a time

when the Bolshevik hold was still far from sure, that there had already been

too much of a delay by the USA in recognizing the Bolshevik regime such as it

existed. The USA had to make up for “lost time,” and like Thompson, Sands considered

the Bolshevik Revolution to be analogous to the American Revolution.[39] In

July 1918 Sands wrote to US Treasury Secretary McAdoo that a commission should

be established by private interests with government backing, to provide

“economic assistance to Russia.”[40]

Armand

Hammer

One of those

closely associated with Ludwig Martens and the Soviet Bureau was Dr. Julius

Hammer, an emigrant from Russia who was a founder of the Communist Party USA.

There is evidence that Julius Hammer was the host to Leon Trotsky when the

latter with his family arrived in New York in 1917, and that it was Dr.

Hammer’s chauffeured car that provided transport to Natalia and the Trotsky

children. The Trotskys were met on disembarkation at the New York dock by

Arthur Concors, a director of the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society,

whose advisory board included Jacob Schiff of Kuhn, Loeb and Co.[41] Dr. Hammer

was the “primary owner of Allied Drug and Chemical Co.,” and “one of those not

so rare creatures, a radical Marxist turned wealthy entrepreneur,” who lived an

opulent lifestyle, according to Professor Spence.[42] Another financier linked

to Trotsky was his own uncle, banker Abram Zhivotovskii, who was associated

with numerous financial interests including those of Olof Aschberg.[43]

The intimate

association of the Hammer family with Soviet Russia was to be maintained from

start to finish, with an interlude of withdrawal during the Stalinist period.

Julius’ son Armand, chairman of Occidental Petroleum Corporation, was the first

foreigner to obtain commercial concessions from the Soviet Government. Armand

was in Russia in 1921 to arrange for the reintroduction of capitalism according

to the new economic course set by Lenin, the New Economic Policy. Lenin stated

to Hammer that the economies of Russia and the USA were complementary, and in

exchange for the exploitation of Russia’s raw materials he hoped for America’s

technology.[44] This was precisely the attitude of significant business

interests in the West. Lenin stated to Hammer that it was hoped the New

Economic Policy would accelerate the economic process “by a system of

industrial and commercial concessions to foreigners. It will give great

opportunities to the United States.”[45]

Hammer met

Trotsky, who asked him whether “financial circles” in the USA regard Russia as

a desirable field of investment? Trotsky continued:

Inasmuch as

Russia had its Revolution, capital was really safer there than anywhere else

because, “whatever should happen abroad, the Soviet would adhere to any

agreements it might make. Suppose one of your Americans invest money in Russia.

When the Revolution comes to America, his property will of course be

nationalized, but his agreement with us will hold good and he will thus be in a

much more favorable position than the rest of his fellow capitalists.[46]

The manner

by which Russia fundamentally changed direction, resulting eventually in the

Cold War when Stalin refused to continue the wartime alliance for the purposes

of establishing a World State via the United Nations Organization, traces its

origins back to the divergence of opinion, among many other issues, between

Trotsky and Stalin in regard to the role of foreign investment in the Soviet

Union.[47] The CFR report had been prescient in warning big business to get

into Russia immediately lest the situation changed radically.

Regimented

Labor

But for the

moment, with Trotsky entrenched as the warlord of Bolshevism, and Lenin

favorable towards international capital investment, events in Russia seemed to be

promising. A further major factor in the enthusiasm certain capitalist

interests had for the Bolsheviks was the regimentation of labor under the

so-called “dictatorship of the proletariat.” The workers’ state provided

foreign capitalists with a controlled workforce. Trotsky had stated:

The militarization of labor is the indispensable

basic method for the organization of our labor forces. . . . Is it true that significant

business interests in the West. Lenin stated to Hammer that it was hoped the

New Economic Policy would accelerate the economic process “by a system of

industrial and commercial concessions to foreigners. It will give great

opportunities to the United States.”[45]

Hammer met

Trotsky, who asked him whether “financial circles” in the USA regard Russia as

a desirable field of investment? Trotsky continued:

Inasmuch as

Russia had its Revolution, capital was really safer there than anywhere else

because, “whatever should happen abroad, the Soviet would adhere to any

agreements it might make. Suppose one of your Americans invest money in Russia.

When the Revolution comes to America, his property will of course be

nationalized, but his agreement with us will hold good and he will thus be in a

much more favorable position than the rest of his fellow capitalists.[46]

The manner

by which Russia fundamentally changed direction, resulting eventually in the

Cold War when Stalin refused to continue the wartime alliance for the purposes

of establishing a World State via the United Nations Organization, traces its

origins back to the divergence of opinion, among many other issues, between

Trotsky and Stalin in regard to the role of foreign investment in the Soviet

Union.[47] The CFR report had been prescient in warning big business to get

into Russia immediately lest the situation changed radically.

Regimented

Labor

But for the

moment, with Trotsky entrenched as the warlord of Bolshevism, and Lenin

favorable towards international capital investment, events in Russia seemed to be

promising. A further major factor in the enthusiasm certain capitalist

interests had for the Bolsheviks was the regimentation of labor under the

so-called “dictatorship of the proletariat.” The workers’ state provided

foreign capitalists with a controlled workforce. Trotsky had stated:

The

militarization of labor is the indispensable basic method for the organization

of our labor forces. . . . Is it true that compulsory labor is always

unproductive? . . . This is the most wretched and miserable liberal prejudice:

chattel slavery too was productive. . . . Compulsory slave labor was in its

time a progressive phenomenon. Labor obligatory for the whole country,

compulsory for every worker, is the basis of socialism. . . . Wages must not be

viewed from the angle of securing the personal existence of the individual

worker [but should] measure the conscientiousness, and efficiency of the work

of every laborer.[48]

Hammer

related of his experiences in the young Soviet state that although lengthy

negotiations had to be undertaken with each of the trades unions involved in an

enterprise, “the great power and influence of the trade unions was not without

its advantages to the employer of labor in Russia. Once the employer had signed

a collective agreement with the union branch there was little risk of strikes

or similar trouble.”

Breaches of

the codes as negotiated could result in dismissal, with recourse by the sacked

worker to a labor court which, in Hammer’s experience, did not generally find

in the worker’s favor, which would mean that there would be little chance of

the sacked worker getting another job.[49]

However,

Trotsky’s insane run in the Soviet Union was short-lived. As for Hammer,

despite his greatly expanding and diverse businesses in the Soviet Union, after

Stalin assumed power Hammer packed up and left, not returning until Stalin’s

demise. Hammer opined decades later:

I never met

Stalin—I never had any desire to do so—and I never had any dealings with him.

However it was perfectly clear to me in 1930 that Stalin was not a man with

whom you could do business. Stalin believed that the state was capable of

running everything without the support of foreign concessionaires and private

enterprise. That is the main reason I left Moscow. I could see that I would soon

be unable to do business there and, since business was my sole reason to be

there, my time was up.[50]

Foreign capital did nonetheless continue to do

business with the USSR[51] as best as it was able, but the promising start that

capitalists saw in the March and November revolutions for a new Russia that

would replace the antiquated Czarist system too was

productive. . . . Compulsory slave labor was in its time a progressive

phenomenon. Labor obligatory for the whole country, compulsory for every

worker, is the basis of socialism. . . . Wages must not be viewed from the angle

of securing the personal existence of the individual worker [but should]

measure the conscientiousness, and efficiency of the work of every laborer.[48]

Hammer

related of his experiences in the young Soviet state that although lengthy

negotiations had to be undertaken with each of the trades unions involved in an

enterprise, “the great power and influence of the trade unions was not without

its advantages to the employer of labor in Russia. Once the employer had signed

a collective agreement with the union branch there was little risk of strikes

or similar trouble.”

Breaches of

the codes as negotiated could result in dismissal, with recourse by the sacked

worker to a labor court which, in Hammer’s experience, did not generally find

in the worker’s favor, which would mean that there would be little chance of

the sacked worker getting another job.[49]

However,

Trotsky’s insane run in the Soviet Union was short-lived. As for Hammer,

despite his greatly expanding and diverse businesses in the Soviet Union, after

Stalin assumed power Hammer packed up and left, not returning until Stalin’s

demise. Hammer opined decades later:

I never met

Stalin—I never had any desire to do so—and I never had any dealings with him.

However it was perfectly clear to me in 1930 that Stalin was not a man with

whom you could do business. Stalin believed that the state was capable of

running everything without the support of foreign concessionaires and private

enterprise. That is the main reason I left Moscow. I could see that I would soon

be unable to do business there and, since business was my sole reason to be

there, my time was up.[50]

Foreign capital did nonetheless continue to do

business with the USSR[51] as best as it was able, but the promising start that

capitalists saw in the March and November revolutions for a new Russia that

would replace the antiquated Czarist system with a modern economy from which

they could reap the rewards was, as the 1923 CFR report warned, short-lived Gorbachev

and Yeltsin provided a brief interregnum of hope for foreign capital, to be

disappointed again with the rise of Putin and a revival of nationalism and

opposition to the oligarchs. The policy of continuing economic relations with

the USSR even during the era of the Cold War was promoted as a strategy in the

immediate aftermath of World War II when a CFR report by George S Franklin

recommended attempting to work with the USSR as much as possible, “unless and

until it becomes entirely evident that the U.S.S.R. is not interested in

achieving cooperation . . .”

The United

States must be powerful not only politically and economically, but also

militarily. We cannot afford to dissipate our military strength unless Russia

is willing concurrently to decrease hers. On this we lay great emphasis.

We must take

every opportunity to work with the Soviets now, when their power is still far

inferior to ours, and hope that we can establish our cooperation on a firmer

basis for the not so distant future when they will have completed their

reconstruction and greatly increased their strength. . . . The policy we

advocate is one of firmness coupled with moderation and patience.[52]

Since Putin,

the CFR again sees Russia as having taken a “wrong direction.” The current

recommendation is for “selective cooperation” rather than “partnership, which

is not now feasible.”[53]

The

Revolutionary Nature of Capital

Should the

fact that international capital viewed the March and even the November

Revolutions with optimism be seen as an anomaly of history? Oswald Spengler was

one of the first historians to expose the connections between capital and

revolution. In The Decline of the West he called socialism

“capitalistic” because it does not aim to replace money-based values,

“but to possess them.” H. G. Wells, it will be recalled, said something

similar. Spengler stated of socialism that it is “nothing but a

trusty henchman of Big Capital, which knows perfectly well how to make use of

it.” He elaborated in a footnote, seeing the connections going back to

antiquity:

It was the Equites,

the big-money party, which made Tiberius Gracchu’s popular movement possible at

all; and as soon as that part of the reforms that was advantageous to

themselves had been successfully legalized, they withdrew and the movement

collapsed.[55]

From the

Gracchuan Age to the Cromwellian and the French Revolutions, to Soros’ “color

revolutions” of today, the Russian Revolutions were neither the first nor the

last of political upheavals to serve the interests of Money Power in the

name of “the people.”

Notes

[1] K. R.

Bolton, “March 1917: Wall Street & the March 1917 Russian Revolution,” Ab

Aeterno, No. 2 (March 2010).

[2] Michael

Pearson, The Sealed Train: Journey to Revolution: Lenin–1917 (London:

Macmillan, 1975).

[3] Paul

Warburg, prior to immigrating to the USA, had been decorated by the Kaiser in

1912.

[4] Col.

William Wiseman, head of the British Secret Service, was the British equivalent

to America’s key presidential adviser, Edward House, with whom he was in

constant communication. Wiseman became a partner in Kuhn, Loeb & Co. From

London on May 1, 1918 Wiseman cabled House that the Allies should intervene at

the invitation of the Bolsheviks and help organize the Bolshevik army then

fighting the White Armies in a bloody Civil War at a time when the Bolshevik

hold on Russia was doubtful (Edward M. House, ed. Charles Seymour, The

Intimate Papers of Col. House [New York: Houghton, Mifflin Co., 1926], Vol.

III, p. 421).